Objects

Overview

Objects in TypeScript, just as in other languages like C#, can be compared to

objects in real life. The concept of objects in TypeScript can be understood

with real-life, tangible objects.

In TypeScript, an object is a standalone entity with properties and type. Compare it with a cup, for example. A cup is an object with properties. A cup has a color, a design, weight, a material it is made of, etc. In the same way, TypeScript objects can have properties, which define their characteristics.

Properties

A TypeScript object has properties associated with it. A property of an object can be explained as a variable that is attached to the object. Object properties are the same as ordinary TypeScript variables, except for the attachment to objects. The properties of an object define the characteristics of the object. You access the properties of an object with a simple dot-notation:

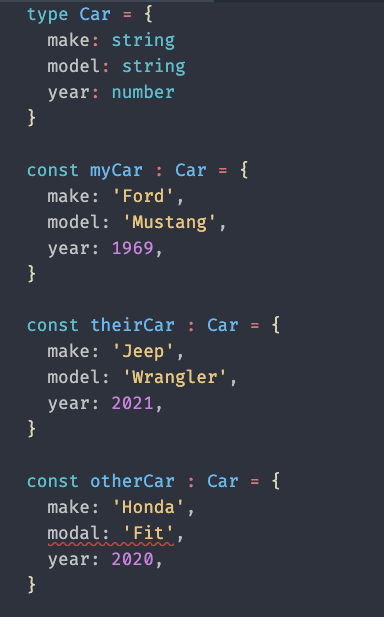

Like all TypeScript variables, both the object name (which could be a normal variable) and property name are case-sensitive. You can define a property by assigning it a value. For example, let's create an object named myCar and give it properties named make, model, and year as follows:

In TypeScript, however, we will receive errors that make, model, and year

are not properties of Object since the default Object type does not know

about them.

A better way to write the above example is with an object initializer, which is a comma-delimited list of zero or more pairs of property names and associated values of an object, enclosed in curly braces ({}):

TypeScript will see that the myCar variable is an object with two string

properties named make and model and one number property named year.

We could continue to make new cars, and as long as we kept the same initial properties, they would all be the same type.

However, this object would not be the same type.

Do you see the problem? The property name for model has a typo!

Using types to find issues in our code

Having defined types is a great way to ensure that we do not make these kinds of errors in our code. A small typo like this could take us hours of time to find! Imagine if our code base was tens of thousands of lines. It might be even longer to find the issue show up.

Define a type

We can teach TypeScript about a new specific type and give it a name of our choice.

Now that we have our type:

With this definition we can clearly see our error:

Accessing properties using bracket notation (and by string)

Properties of TypeScript objects can also be accessed or set using a bracket

notation. So, for example, you could access the properties of the myCar object

as follows:

An object property name can be any valid TypeScript string or anything that can be converted to a string, including the empty string.

However, any property name that is not a valid TypeScript identifier (for example, a property name that has a space or a hyphen or that starts with a number) can only be accessed using the square bracket notation.

This notation is also very useful when property names are to be dynamically determined (when the property name is not determined until runtime). Examples are as follows:

Warning about the [] notation in TypeScript

TypeScript does not check our object type when using this operator, so be cautious when using it.

Using a variable to indicate a property name

Let's say we had, in a string variable, the name of a property we wish to set on

an object. However, instead of the case above where we set the value of an

existing object (e.g. myCar[propertyName] = 'Mustang'), we wanted to create a

new object and use the variable to indicate what property to set.

We could do something like this:

In this case, myOtherCar would be { model: 'Mustang'}.

While this doesn't seem particularly powerful when combined with the technique below, we get a fairly powerful pair of features we'll be using later.

Making a new object from an existing one

Let's take our car example again:

If we wanted to make another instance of this object, but with a different

year, we could do something like this:

And now we would have a new object, independent of the first, with a different

year. However, you could imagine that if we had many properties, it would be

cumbersome to repeat all the keys and values. Fortunately, TypeScript allows for

a shortcut to "expand" all the keys and values. This is known as the spread

operator and is noted as ...

So let's write this again using the spread operator:

Much better, we've saved one line of code, however, it now doesn't matter how

many property/value pairs myCar has since they are all now part of

myOtherCar since this is effectively what TypeScript is doing for us:

You'll notice that the year from myCar is added to the object. However, our

code outside of the ...myCar introduces a value for year again. Since this

comes after the spread operator, our value of 1971 overrides the one from

year: myCar.year

NOTE: The order is important!

If we wrote the code like this:

In this case, our property/value pair of year: 1971 would be lost since the

... spread would reintroduce the value from myCar

Resources

For more details on objects, see this article or this quick reference guide.